The Science of Reading is More Than Foundational Skills

In the last few years, there’s been a resurgence of attention to the importance of the science of reading. States and school districts are increasingly recognizing the pivotal role of these practices. Yet, if we’re not careful, this very progress may undermine other important aspects of reading instruction.

There is no doubt that the instruction and weekly assessments of foundational reading skills, including letter names and sounds, phonological awareness, phonics/decoding, and fluency, are critical and necessary. Without this instruction and continuous monitoring of these foundational skills, students struggle to independently read and comprehend text.

The goal of the science of reading, however, is not just to decode words, but to allow students to make meaning of what they read. In fact, the old saw – that students learn to read and then read to learn – doesn’t get it right. “Students can and should do both at the same time” (Myracle, 2022) if we want them to be motivated to read and to enjoy reading.

State Support for Evidence-Based Approaches to Early Literacy

In just the past two years, 26 states and the District of Columbia announced plans to use COVID-19 relief funding through the American Rescue Plan, or previous aid packages, to support teacher training or instruction in evidence-based approaches to early literacy (Schwartz, 2022). Likewise, in the last three years alone, 18 states and the District of Columbia passed new laws or enacted regulations that require teachers to learn, and use, techniques grounded in the large body of research on how children learn to read. (Schwartz, 2022). More than a dozen enacted such laws between 2013 and 2019 (Schwartz, 2022).

Promises to ground reading instruction in science may seem familiar to some. The No Child Left Behind Act, enacted in 2002, required schools to use “scientifically based reading research.” Under this policy, foundational skills instruction became the key component of literacy instruction with little time for vocabulary instruction, building background knowledge, or developing comprehension skills.

We Need to Go Beyond Instruction in Foundational Skills

Given the science-of-reading research and the promotion of programs focused on these foundational skills, it is imperative for state and district educators to remember that students in grades K-3 need more than just instruction in foundational skills to become active and motivated readers.

Simultaneously engaging students in rich texts that coherently build knowledge and vocabulary, such as through narrative or informational science, or history read-alouds or videos, allows them to grow knowledge, enhance vocabulary, and increase comprehension skills (Student Achievement Partners, 2021). Whole-group and small-group collaborative discussions, and formatively assessing comprehension, should be integral aspects of literacy instruction.

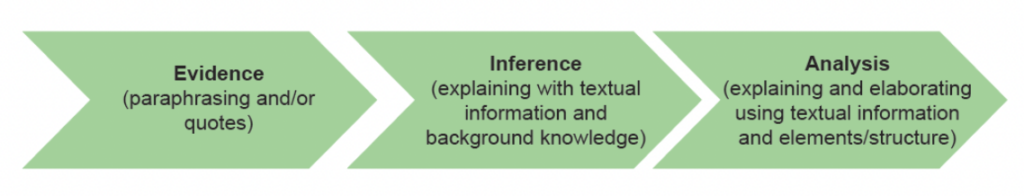

Text-based comprehension questions that engage students in discussions of text must move beyond the superficial into analyzing the text. We define analysis as a detailed examination of the elements or structure of text, by breaking it into its component parts to uncover interrelationships in order to draw a conclusion (Thompson & Lyons, 2017).

Some may think this work is too difficult for students in grades K-2. But our exploratory study with the Pennsylvania Department of Education, Pennsylvania teachers, and students in K-2 revealed that when teachers unpacked the underlying knowledge and skills of the reading standards and how they lead to text analysis, they were able to develop close-reading lessons for texts read aloud.

These lessons included text-dependent questions focused on the underlying knowledge and skills of the reading elements in the Pennsylvania Academic Standards such as characters, setting, and events, and how they work together in a story. Teachers supported students in using text evidence and their background knowledge to make inferences, and to ultimately make sense of what the author is saying, as illustrated below.

Students were able to demonstrate deeper comprehension of richer texts without decoding impeding their ability to make inferences and demonstrate deep understanding of the text.

To be clear, no part of this argument suggests that foundational skills shouldn’t be taught and assessed. Our study is a reminder that students are capable of moving beyond decoding to comprehend and discuss texts’ deeper meanings as students learn to read independently.

Example analysis questions included:

- Grade K: How did the details show what happened in the beginning/middle/ending of the story?

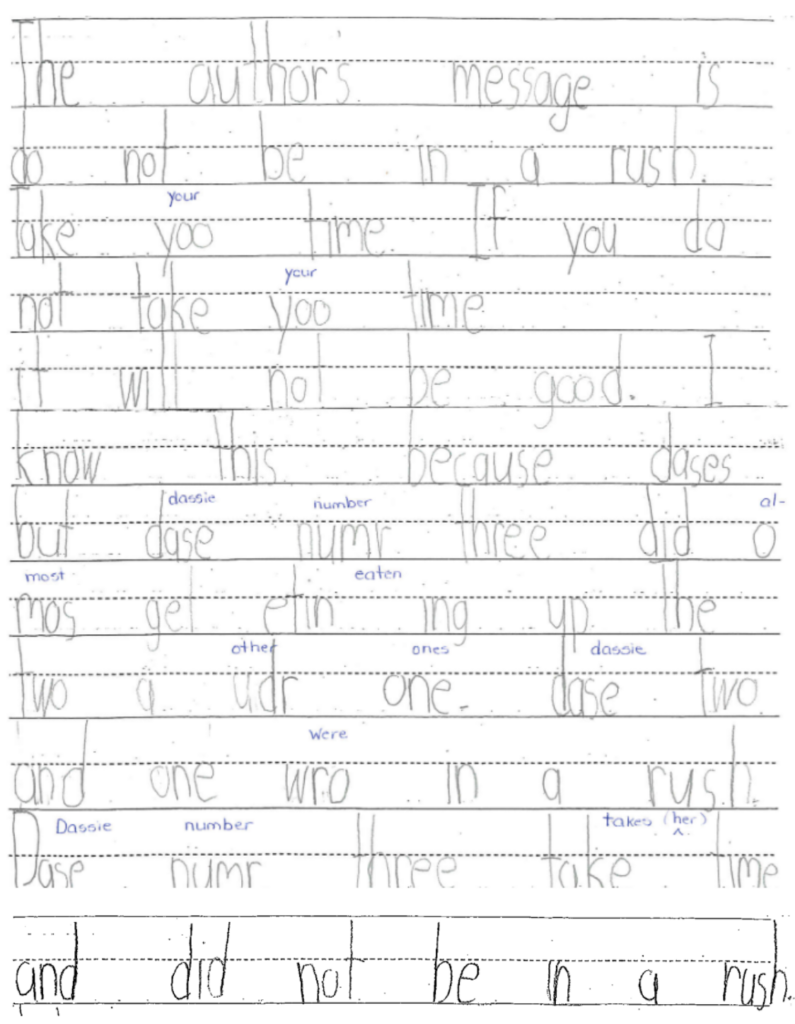

- Grade 1: What was the author’s message in the text ____?

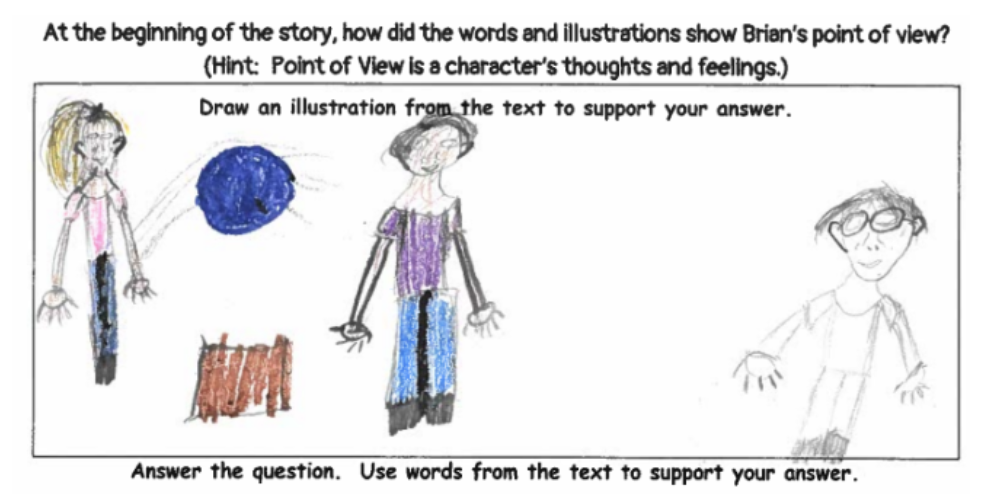

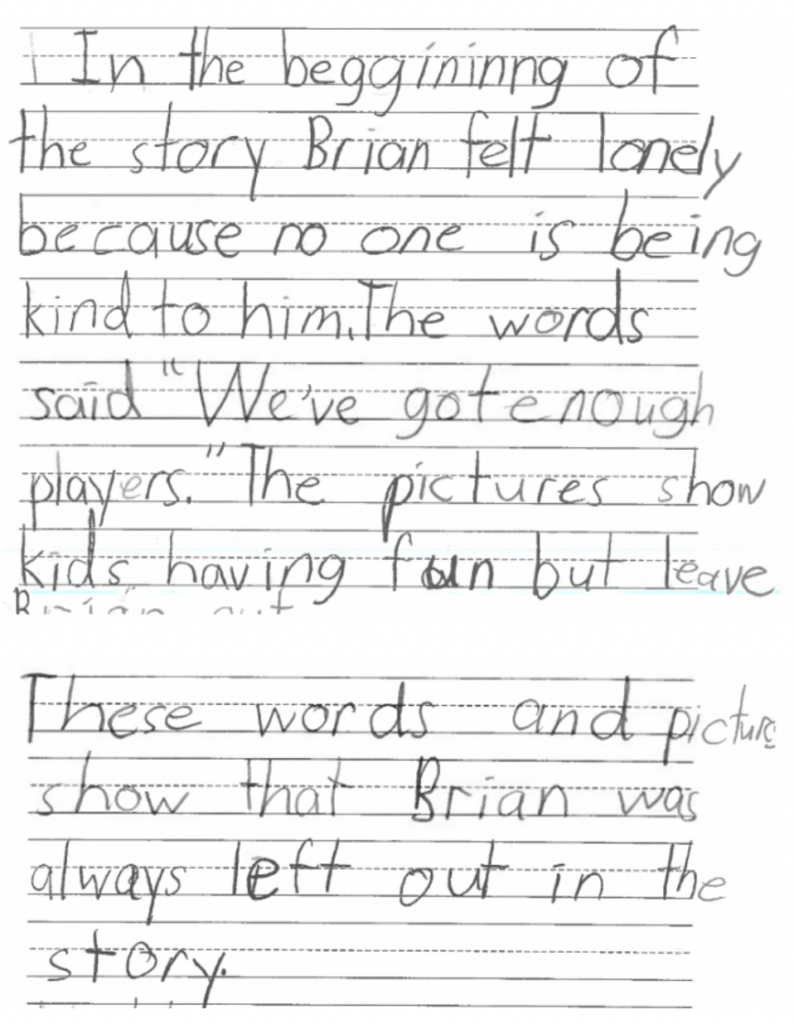

- Grade 2: How did the words and illustrations in the story,____, show how the character’s point of view changes from the beginning to the end of the story.

Strategies used to support students’ demonstration of analysis included sentence starters (e.g., The author’s message is ____ and I know this because_____.) and graphic organizers.

At the end of the year, after 1st grade teachers read a text aloud, students were asked to discuss and respond to the question about the author’s message. An example response is below (Thompson, 2022).

While some students may not be ready to respond in writing, research supports that asking students to write about the texts they are reading increases comprehension (Graham & Hebert, 2010, Achieve the Core, 2021). Asking students to write about what they read as a formative assessment process allows teachers to provide students with feedback on both comprehension and writing, and these writing samples can be used to drive instruction along an appropriate learning pathway (Thompson, 2022). Nonetheless, this student’s written response comes after a year of learning foundational skills, as well as comprehension of texts. The student can demonstrate a general comprehension of the text, make inferences, and use evidence to support the explanation of the author’s message.

This 2nd-grade student used a graphic organizer and writing to explain the character’s point of view.

Our study shows that young children are ready to create meaning out of what they read, and their lives are enriched by it.

Helping Children Learn to Love Reading

If children are going to learn to love reading, we need to help them understand how to break its code to derive meaning from the text and use this information to make meaning of the world around them. This newfound skill is what allows children to continue learning long after they have left the formal education system.

The benefits of loving reading are innumerable and well-established. It helps us make sense of the world around us and leads us to seek out new knowledge and to apply it in our lives. Reading can help us find new solutions to old problems, enjoy our work, and enrich our lives. Loving reading can foster a love of learning in general.

Students as young as five years old have a wealth of knowledge that can and should be used to make meaning of text. Educators don’t have to choose between teaching foundational skills and building a love of reading. We can and should do both. Now, with so many children suffering the academic setbacks of COVID-19, it’s more important than ever.

The post Let’s Not Repeat the Past Mistakes in K-12 Reading Instruction and Assessment appeared first on Center for Assessment.